On a breezy January evening, Tristian Castleman stood on the banks of the James River and faced the setting sun.

He donned a pair of sunglasses and blinked. Then he smiled. It was the first time the 19-year-old had seen a sunset in its true colors.

“Cool,” he said, grinning the whole time.

The Williamsburg teenager is one of an estimated 300 million people around the world who are colorblind, also known as color vision deficiency. Like most people who have the condition, Castleman is red-green colorblind, which makes hues of red and green hard to see. But other colors in the normal color spectrum can be off as well.

Reds and greens usually come across as brown. Purple might look blue. Pink appears as gray.

Thanks to the special pair of sunglasses Castleman now has, he can see all those colors.

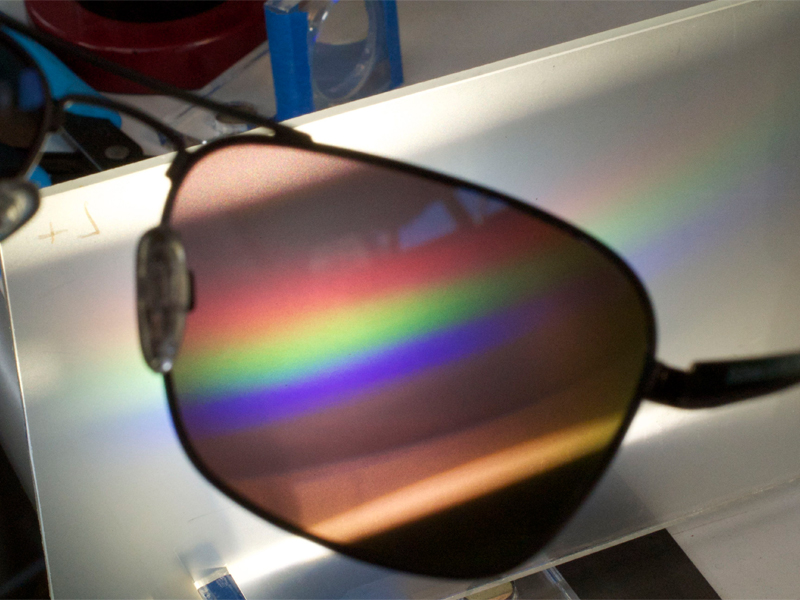

The high-tech specs are made by a California-based company called EnChroma, which has distributed some 25,000 pairs of their glasses since they were introduced to the public in 2012. They do not cure colorblindness, but they boost and improve color vision for the colorblind.

“The glasses add more depth,” says Kent Streeb, an EnChroma spokesperson. “People will say that before, grass just looked like a brush of color. This helps them see shades of green.”

Castleman received the glasses—thanks to an anonymous donor—after he entered a contest sponsored by EnChroma and the Clorox Company. The two companies wanted to get EnChroma glasses into the hands of colorblind schoolchildren across the country.

According to EnChroma, many colorblind students struggle in school because so much information is color-coded, especially in the first 10 years of a child’s life. Think about picking the right crayon in kindergarten.

Or choosing colored blocks on a worksheet.

“It is important to get EnChroma eyewear to as many colorblind children as possible to level the playing field at school,” says Tony Dykes, EnChroma’s CEO, earlier this year.

That EnChroma glasses help the colorblind was actually an accident. Company co-founder Don McPherson, a glass scientist, originally intended his glasses to help protect surgeons’ eyes from lasers and to help differentiate human tissue. He happened to have the glasses on while playing Frisbee with a friend, and the friend asked to try them on.

The friend, who was colorblind, put the glasses on and could see colors he had never seen before. That sparked a new idea for McPherson, who obtained a grant from the National Institutes of Health to learn more about color vision and how special glasses might help. The first glasses were introduced to the public in 2012, selling for $700.

Later improvements allowed the company to drop the price, and they now range from $250 to $450. Adult and child models are available in sunglasses, regular glasses, a hybrid between the two, and can be made to fit prescriptions that correct vision.

When someone is colorblind, cells in the retina that enable the brain to perceive color are abnormal. The most common deficiency affects the red and green cones in the eye, although blue-cone abnormalities also exist. There is such a thing as total colorblindness, in which someone sees only black and white, but it’s very rare.

EnChroma’s glasses are for those with red-green color vision deficiency—they work by re-establishing the correct balance between signals from the three photo pigments in the eye. In a normal eye, the green and red photo receptors overlap, while in the colorblind, the overlap is even greater, causing distinct hues to become indistinguishable.

The glasses help that. They work for four out of five people who try them, EnChroma’s Streeb says.

There are competitors who also make glasses geared to help the colorblind, but Streeb says those are usually lenses that are simply tinted pink or red, which can help shades “pop” out from each other. The EnChroma glasses, Streeb says, let people actually see the nuances in the shades, not just that there’s a difference between them.

For Castleman, the glasses are allowing him to see colors he never saw before. Pineapples had always looked brown to him—with the glasses on, they’re green. Radishes looked brown—now they’re red. It wasn’t until he looked through the glasses that he realized the colors of the College of William and Mary are green and yellow, and not brown and yellow.

And an American flag? It now looks red, white and blue, instead of brown, white and blue.

“When he tried them on for the first time, he said, ‘Wait, it’s green?’ while pointing to the bottom stop light,” says his mother, Stephanie Castleman. “Before, it was just illuminated. It was just white.”

Castleman recently received a second pair of glasses, this time a clear pair that he can use indoors. He’s currently away at Wisconsin’s Shepherds College, which offers a program for the intellectually disabled. Castleman, who graduated from Jamestown High School (where he was the mascot for four years), is attending a program there that will allow him to become more independent while at the same time study the culinary arts.

His mom says she can’t wait for Tristian’s return home this summer, when he’ll be able to see much more than the stark brown trees he saw over the winter.

“I can’t wait,” Stephanie Castleman says, “for him to see flowers.”

Take EnChroma’s online test to see if you could be colorblind:

www.enchroma.com

See Tristian Castleman try on EnChroma sunglasses for the first time:

https://youtu.be/F3mGZAqctZA

And see a sunset for the first time:

https://youtu.be/Z78Aqa2i5E8

Want to see what life is life for the red-green color blind?

Download the Chromatic Vision Simulator app on the iTunes App Store.