Part 2: How to escape the addiction

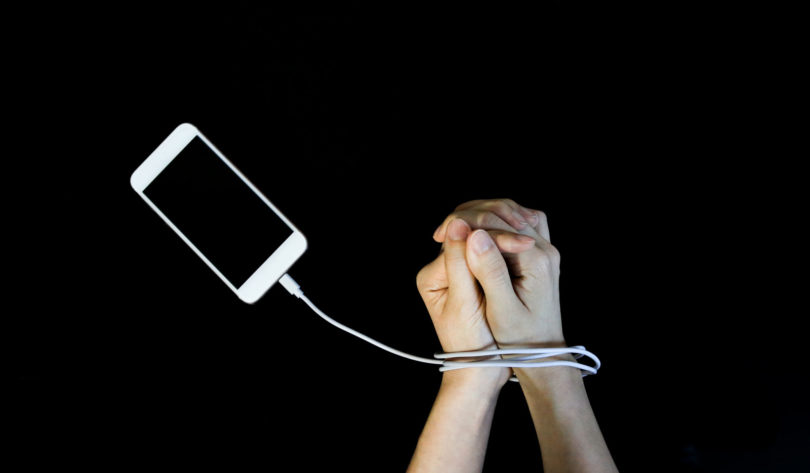

Soon after writing part one of this series, feeling certain that I was not on the spectrum of ITD (Internet technology dependence), I dropped my iPhone off at a local office supply store to have the cracked screen replaced. Driving out of the parking lot I felt a strange sense of freedom at the thought that I now had a perfect excuse for not being easily accessible. This was quickly replaced by the anxious realization that I would not be able to immediately connect with anyone should I need to. This back and forth went on for a better part of the day and ended when I was reunited with my phone and its fresh non-cracked screen. My first act, once I was back online, was to ask Siri to remind me to go back and reread part one of this series and take the “are you addicted” test.

The jury is still out on whether or not future generations will look back on today’s concerns about people getting hooked on “likes” with a shrug of “What was all the fuss about?” or with a sigh of “How could they not see the problem?” What is clear is that social media use is not going away, nor will a surgeon general attach a warning emoji to it any time soon.

The power to instantaneously connect with anyone anywhere on the globe is nothing short of miraculous. It is hard to argue with the list of pros that include ending isolation, contributing to the social welfare of the masses, quickly disseminating vital information and creating bonds beyond national borders. Advocates can readily make the case that for every identified negative, there is an actual workplace solution to the problem (on-line meetings for people who suffer from compulsive Internet use or apps that track how often one checks in online are just two examples). Social media is not the first, or last, problem-solver to create more problems only to become a solution when in the right hands.

Just what constitutes the wrong hands is where things get tricky. It should certainly set off alarms that some of Information Technology’s giants, to include Bill Gates and the late Steve Jobs, limited the use of their creations within their own families. Recent headlines have pointed to the disastrous effects when face-to-face bullying goes digital and causes harm across great distances. Additionally, most reasonable people agree that children need extra protection from the dangers of social media use and that teenagers, who are known to take things to extremes, are at heightened risk for abuse.

When we move into the adult world, we confront the age-old conundrum that is the undercurrent of most addiction debates: “How do we protect people from themselves?”

Within the field of chemical addiction, the question of what to do when habit becomes addiction is answered by dropping the need to apply a label and deal with the impact. If what you’re doing is harming yourself and/or others, the question of what we call it is not as important as what we’re going to do about it. For chemical addiction, this meant expanding treatment interventions and acknowledging that those struggling with substance abuse often have co-occurring mental health issues.

The rise of treatment centers specializing in treating Internet addictions is still in its infancy, and anyone considering that route should do the same homework they would when choosing any form of treatment. A more readily accessible option would to turn to outpatient counseling. Many therapists who have been trained to treat chemical addictions and compulsive behaviors are adapting these techniques to address this latest manifestation of when good habits go bad. A quick search of the Psychology Today website is a great way to filter search for local providers who have unique skills in this area.

For those who take this psychotherapeutic path, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) will most likely be the intervention of choice. This well-researched approach seeks to free clients from dysfunctional patterns of behavior by exposing the thinking errors that drive habits and addictions. Rather than teaching total abstinence as a means of extinguishing the behavior, a CBT therapist helps the client correct the cognitive distortions that are breathing life into dysfunctional patterns of behavior (i.e. the belief that my self-worth is determined by how many likes my recent post received) and replace them with thoughts that contribute to healthier life choices.

For those who feel that their digital life has become unmanageable but prefer a self-help approach, a good start would be to take a page from our friends in Alcoholics Anonymous. Since AA and its 12-step program remain the backbone of many addiction-treatment models, one would be in good hands while attempting to bring a sense of sanity and serenity into one’s life.

As the debate continues regarding the possible negative impacts of social media use, all of us would be wise to take stock of how we use these platforms. While most people will likely never fall down the rabbit hole of getting hooked on likes, many will discover the somewhat unnerving realization that in the words of poet T.S. Eliot, we are using Internet culture to be “distracted from distraction by distraction” and that its overuse is “filled with fancies and empty of meaning.”

Part 1: #hooked on likes