Written by Alison Johnson

Photo by Brian Freer

Stephen Chantry never pushed his kids to run. He didn’t lecture them on what it takes to be an elite runner—not just a few hard workouts here and there, but a training plan that included cold and rainy days, days when they had too much homework or hadn’t gotten enough sleep, days when they weren’t sick but just didn’t feel like running.

Instead, he showed them.

It all started at a family meeting about nine years ago in their Williamsburg home, when Chantry told his wife, Dee-Dee, and their three children that he dreamed of becoming a world-class master’s runner. He wanted them to understand exactly how much time that would take. He needed them to support his twice-daily runs and travel to different races, which he couldn’t always work around family events.

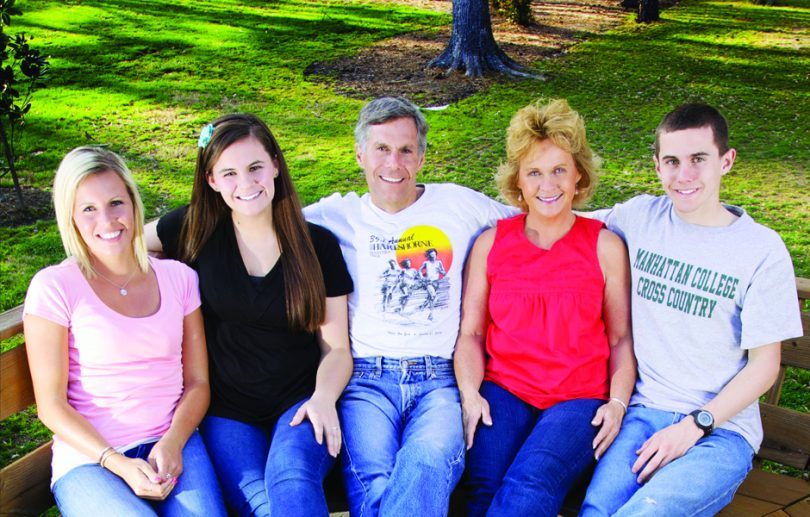

Dee-Dee, Jacquelyne (far left in photo), AnnaLeah and Stephen Jr. told him to go for it. Then they watched Chantry transform himself into an elite track athlete in 50-plus age divisions. “My dad just decided he wanted to see exactly how far he could go if he gave it his best,” Jacquelyne says. “He made a goal and stuck to it. I was in 8th or 9th grade, and I remember thinking how cool it was that he was going to push himself so much. I think we all wanted to be like him. I’m still trying to be like him now.”

As it turned out, Jacquelyne and Stephen would inherit Chantry’s passion for competitive running. At first, they jogged mainly to get in shape for other sports and spend more time with their dad. As they got faster, the siblings excelled in track and cross-country at Lafayette High School in Williamsburg and both became college athletes. At 19, Stephen now is a top young runner at Manhattan College in New York. Jacquelyne, 23, earned a full scholarship to Longwood University, continued running in graduate school and was an assistant coach last fall at Christopher Newport University in Newport News. She now works as a fitness expert at American University in Washington, D.C.

The more miles that father, daughter and son logged—especially when they got to run together

—the closer they became.

“We have so much fun,” says Stephen Sr., 57, now a distance coach for the indoor and outdoor track program at Lafayette High School. “Sometimes we can get a little competitive with each other, but mostly we can just cruise along and talk. Unless we’re really pushing ourselves, it’s pretty effortless. I call it ‘sitting on our legs and going for a ride.’”

The father

Stephen Chantry Sr., has been running for 42 years. He competed in high school and on cross-country and track teams at St. Lawrence University in Canton, N.Y. He kept in shape as he earned a master’s degree and doctorate from the College of William and Mary and took a job with the Williamsburg-James City County public school system. There were some setbacks, such as a 1976 car accident in which he crashed through the windshield and suffered head lacerations and a knee injury after another driver ran a red light. “Things fell apart for a while,” he says. “For quite a while, I was only an OK runner.”

Once Chantry decided he wanted to be a top runner in his age division, however, he quickly got serious.

By the time he hit the 50-to-54 age group, he was winning national titles in multiple events. Those included the 800-meter, mile and 3,000-meter events at the 2006 United States of America Track and Field (USATF) Indoor Nationals and the mile, 3,000-meter and 5,000-meter races at that meet in 2007. His 2006 time in the 3,000-meter (1.86 miles), 9:23:65, was the fastest in the world that year for his age group.

Now in the 55-to-59 age group, Chantry’s titles have included the 1,500- and 3,000-meter races at the 2010 World Masters Indoor Championships and, most recently, the 3,000-meter at the USA Indoor Track National Master’s Championships in March. As a member of the Colonial Road Runners club in Williamsburg, he also has run many races locally and statewide; last year, he was inducted into the Virginia Peninsula Road Racing Hall of Fame.

The key to success, Chantry says, is basic hard work—the message he passed along to his kids. He runs anywhere from 50 to 90 miles a week, mixing in slower and faster intervals and “rest” days that might involve six miles at an easy pace. “Talent will always be caught by people who train well,” he says. “The hardest part is developing a plan and sticking with it, day after day. Anyone can run one or two hard workouts. The question is: will you do the hard workouts every time you’re supposed to? There’s no quick fix, no magic pill.”

Chantry also is quick to credit his tight-knit family for their support, especially his wife, a kindergarten teacher who shouldered many family responsibilities when Chantry was off training and racing (and whipped up plenty of pre-race pasta dinners). While daughter AnnaLeah, a talented artist, didn’t catch the competitive running bug, she runs for fitness and has come to many of her father and siblings’ events. As for Jacquelyne and Stephen’s running careers, Chantry is just a proud father.

“It’s neat to see how good they’ve gotten,” he says. “Stephen can beat me now! He does these absolute monster workouts—I don’t think I’ve ever done that much. And with Jacquelyne, female distance runners usually don’t peak until their mid-30s. I am just excited to see where she goes.”

The daughter

At first, Jacquelyne didn’t think much about running as a sport in itself. She was a basketball junkie, a 5-foot-8 guard, and wanted to be quicker on the court. Her father was a powerful example as an athlete; Jacquelyne had seen him go from average to excellent through sheer determination. So she asked if he would run with her.

On one of their first outings, when Jacquelyne was about 13, Chantry told her she’d run three miles—then an impressively long distance for her—as motivation. She later discovered they’d only done two. Gradually, Jacquelyne realized that she was actually better at running than basketball. “Running came easier to me than any other sport,” she says. She also loved it: “It was something I could do for myself every day, whether with my friends or alone, and let my stress go. And I’m super-competitive, so even if the training is hard, I am willing to do it because I want to do well in races.”

Jacquelyne ran all four years at Lafayette and then at Longwood, where she was the school’s top runner for her last three years, set school records in the indoor mile and outdoor 1,500 meter and served as team captain during her junior and senior seasons. She majored in kinesiology, or the scientific study of human movement. After graduating, she kept competing at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, where she earned a master’s degree in exercise science. Personal highlights included running a 6K, or 3.7-mile race, in 22 minutes, 54 seconds and a 1,500-meter event—just under a mile —in 4 minutes, 56 seconds.

Last fall, Jacquelyne worked as an assistant cross-country and track coach at Christopher Newport Universiy. In her current job, fitness facility coordinator at American University, she manages personal trainers and group exercise instructors. She also has used her fitness expertise to help her father improve his core body strength, designing an exercise plan to target his arms, shoulders, abdominals and back.

“We talk about workouts all the time,” Chantry says. Adds Jacquelyne: “I’m really close with my mom on other things, but running is like this cool little bond that I have with my dad. I am aware that there aren’t many daughters and fathers who can have a sports bond like that.”

Jacquelyne still runs almost daily (she jokes that she loves desserts, particularly her mother’s chocolate éclair cake, too much to stop), covering anywhere from 40 to 60 miles a week. She recently ran a 5K with AnnaLeah, 22, who is studying to become a teacher at Longwood. Whenever she can, Jacquelyne heads out with her father and little brother, who, she reluctantly admits, can dust her these days.

“My dad is so knowledgeable, and he and Stephen are so disciplined with their running,” she says. “I’ve had some times where I feel like I’ve gotten to that point, but I also still feel like I’m trying to be as good as they are. We push each other. They inspire me.”

The son

Where Jacquelyne’s favorite sport as a child was basketball, Stephen Jr. favored baseball. He and his dad originally bonded more in the garage, working on machinery ranging from lawnmowers and cars and planning projects such as building a deck at their home. But like Jacquelyne, Stephen was watching Chantry’s running progress with awe. When he hit middle school, he decided he’d be a runner, too.

“I wanted to do it so I could be like my dad,” he says. “At first it was painful and I didn’t think I could finish our runs. A few times he’d lie and say we were doing two miles but then go out four miles before we turned around. For a while, I was breathing too hard to talk much with him.”

His father had a famous quote that Stephen often thinks about during races: “It hurts just as much to go slow.” In other words, Stephen could push himself to finish a race faster and be happy at the finish, or he could slow down, still be in pain along the way and then be upset with himself when he was done. Stephen wrote the quote on an identification card he keeps in his shoe when he runs. “The words go through my head and I can hear my dad saying them,” Stephen says. “They keep me on pace.”

At college, Stephen specializes in distance running, ranging from 3K indoor track races to 10K outdoor events. A highlight from his first year was posting the fastest 3K (1.86 miles) time for a freshman, 9:03. He juggles two-hour daily practices with a major in mechanical engineering and possible minors in math and business (and, when he can, 30-minute naps to refresh his energy). He says his dream job would be an engineer at BMW.

Like Jacquelyne, Stephen plans to keep running long after graduation. He doesn’t even mind heading out in the cold and rain. “There are a few days I don’t want to go, but mostly it’s just relaxing to me,” he says. “It’s like my dad says: sit on your legs and go

for a ride.”

For other parents hoping to inspire their families to be more active, Chantry advises setting a good example—his wife, he notes, isn’t a runner but usually swims five days a week, and the whole family is into water sports—and simply getting kids outside to play. “Too often, less active youngsters are inside, and they tend to let their electronic games play while they watch,” he says. “They don’t have to do anything prescribed outside. The concept of ‘play’ is unstructured activity. Sometimes you will observe children sitting for a while wondering what to do—and then they rise and start playing some game.”

Or like his kids, they rise and start running.

—–