Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers that affects men, with more than 240,000 cases diagnosed each year.

Fortunately, it’s also very curable. In the past 25 years, the five-year survival rate for all stages has jumped from 69 percent to nearly 100 percent, according to the American Cancer Society.

Treatment for prostate cancer, which affects a walnut-sized gland found in the male reproductive tract, is constantly improving. There are several options that exist once a diagnosis is made. Sometimes, a doctor might decide the cancer doesn’t need to be treated right away. Other times, surgery or radiation therapy might be called for.

There are two broad categories of radiation therapy—internal and external. Both are designed to target the tumor while minimizing exposure to surrounding tissue. Internal radiation therapy, or brachytherapy, treats cancer with radioactive seeds that are placed inside the body at the treatment area. External therapy administers radiation through high-energy beams.

Fauquier County, Virginia, resident Mike Jones had already had surgery to remove his prostate last year when doctors realized his PSA, or prostate-specific antigen, numbers weren’t going down. A PSA blood test and digital rectal exam can help identify prostate cancer in its early stages; PSA levels are also tracked followed treatment.

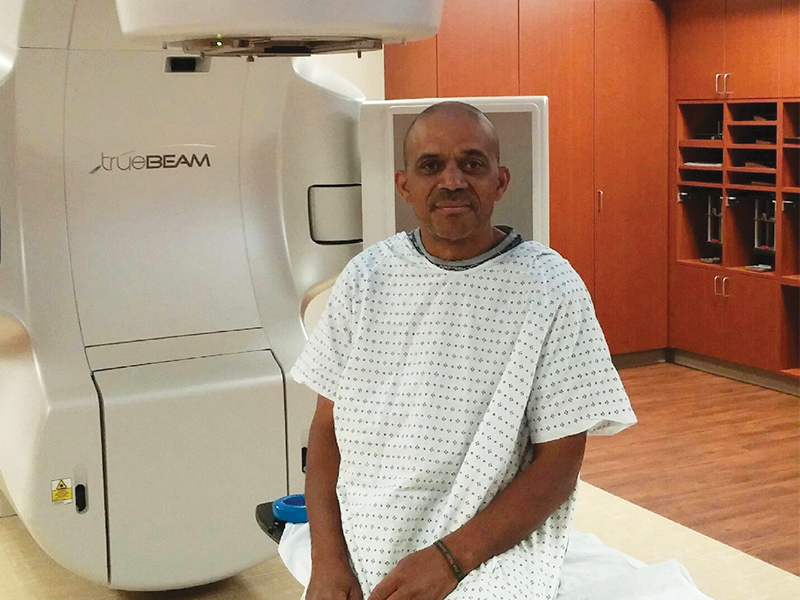

Jones chose to have a form of external radiation therapy called IMRT, or intensity modulated radiation therapy, at the Novant Health Cancer Center in Gainesville, Virginia. This technique uses 3-D scans of the body to guide the beams of radiation to a tumor from many different angles resulting in less exposure to healthy tissue.

Jones, 57, went for eight weeks’ worth of radiation therapy—five days a week, 10 minutes at a time—before finishing his treatment in June. Each time, he had to lie still while the machine, a linear accelerator, rotated twice around him. Jones was able to use the Novant center’s latest machine, which is able to penetrate a tumor even more than before.

Jones will have to have his PSA numbers checked again in October to make sure the treatment worked. His radiation oncologist, Dr. Sanjeev Aggarwal, was “pretty confident,” Jones says. “He said it would work. I’m hoping he’s right.”

At the Novant center, doctors use a type of image-guided treatment called RapidArc, which is able to deliver radiation two to eight times faster than previously possible. Faster treatments are good for patients: one, they’re more comfortable, not requiring the need to be still for as long, and two, they’re more accurate. RapidArc can deliver a beam the size of a pencil tip.

RapidArc uses computer-generated images to plan and deliver the necessary dose of radiation. While a patient is lying flat, the machine revolves around him, rotating 360 degrees as it delivers the radiation where it needs to go, adjusting the beam as needed. RapidArc delivers its dose in a single rotation, taking only about two minutes.

Aggarwal, the cancer center’s medical director, helped bring RapidArc to the Washington, D.C., area. The treatment system is used to treat various types of cancer, including brain tumors, breast cancers, pancreatic cancers and rectal cancer.

“We have pioneered the use of innovative technologies,” Aggarwal says.

In Hampton Roads, Virginia, the RapidArc system is available at Bon Secours’ Martha W. Davis Cancer Treatment Center in Portsmouth. Other cancer centers offer various ways of treatment.

The Hampton University Proton Therapy Institute uses protons as part of its radiation therapy. Traditional radiotherapy uses photons, which are like X-rays (also used with the CyberKnife at the Sentara Advanced Radiosurgery Center at Norfolk General Hospital.) Both methods treat tumors similarly, damaging the DNA and inhibiting the growth of cancer cells. Proton therapy, however, is able to drop the bulk of its energy right at the tumor, with the intent of limiting exposure to healthy tissue.

Not damaging surrounding areas is a big goal when treating prostate cancer. The prostate is located close to the bladder and urethra, which is the tube that carries urine from the bladder. When Jones did his therapy, he had to first drink 42 ounces of water to keep the bladder away from the rectum.

Overall, however, “it was a painless treatment,” Jones says.

Although it’s sometimes a delicate subject for men, Jones—a married father of three grown children and grandfather to three— says he highly recommends all men start getting prostate exams after age 50. He had been having exams done every year with his physicals when his prostate showed signs of swelling early last year. His doctor quickly investigated further, allowing his cancer to be caught early.

All men are at risk for prostate cancer, and the risk gets stronger with age. Nearly two-thirds of all prostate cancers are diagnosed in men over the age of 65. Prostate cancer is also more common among black men. The prevalence of prostate cancer in Hampton Roads—where more men die from it than anywhere else in the country—is one factor that led Hampton University to build its proton therapy institute.

“If anyone is 50, I strongly recommend you get the exam,” Jones says. “Whether you want to know or not. The amount of technology they have these days, you have options.”