Written by Kim O’Brien Root—

A tiny little body part that has no use is one that can cause a big problem.

The left atrial appendage is a small muscular pouch connected to the left atrium— one of the upper chambers of the heart. Like the appendix, there’s no known function for this appendage.

Normally, as the heart pumps, the appendage squeezes rhythmically, pumping out blood into the left atrium, where it’s then sent throughout the body. Everyone has appendages of various sizes and shapes connected to left and right atriums.

The appendages form embryologically—in the womb—in the top and bottom chambers of the heart to control blood flow. Then they just stick around, often causing no problems. But sometimes, they can get in the way.

In people with an abnormal heart rhythm, the blood inside the appendages can become stagnant and clot if the appendage doesn’t contract correctly. If a clot forms in the right atrial appendage, it goes to the lungs and usually isn’t noticed. But if a clot breaks off from the left atrial appendage, it travels to the brain and causes a stroke.

For those who suffer from atrial fibrillation—the most common form of abnormal heart rhythm—the risk of stroke is a huge worry. Patients diagnosed with the condition, which causes the heart to beat too fast or too slow, are five times more likely to have a stroke. Those strokes, when they happen, are almost always caused by a clot formed in the left atrial appendage.

“It’s not a nice feeling,” says Virginia Ellenor, a 71-year-old Portsmouth woman who’s been living with atrial fibrillation for several years. “Every day you’re living with the fear of having a stroke.”

So in June, Ellenor became the first person at Bon Secours Maryview Medical Center in Portsmouth, Va., to undergo a new non-surgical therapy aimed at reducing stroke risk for patients with atrial fibrillation. The hospital is the first in Hampton Roads to offer the procedure. Some 6 million Americans, particularly the elderly, suffer from atrial fibrillation, which results in symptoms of heart palpitations, shortness of breath or lightheadedness. Typically, patients with atrial fibrillation take blood-thinning medication to keep clots from forming. But not everyone can tolerate those medications—such was the case with Ellenor, who experienced gastrointestinal bleeding.

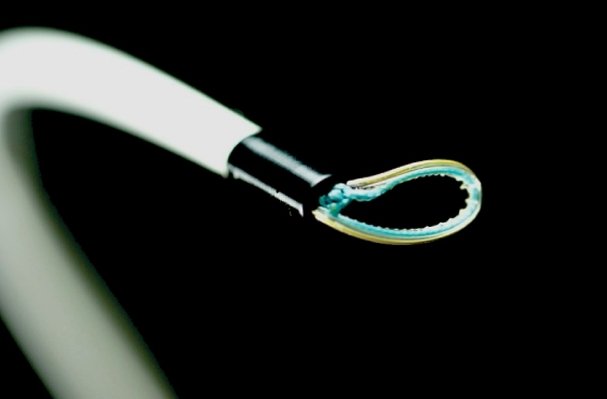

The LARIAT Suture Delivery Device, approved by the FDA last year, is used in a method that ties off that pesky appendage, permanently sealing it off from the rest of the heart. Doctors use two catheters during the procedure—one that guides a wire up from the groin, and a second that places the LARIAT under the patient’s rib cage.

The wire cinches the neck of the appendage off as a lasso would, leaving a dissolvable suture behind. Closed off and with no blood flow, the appendage is gradually absorbed by the body, says Dr. Ryan Seutter, who performed Ellenor’s surgery with fellow Bon Secours Heart & Vascular Institute cardiologist Dr. Jun Chung.

“Preventing stroke has been a big challenge in treating patients with atrial fibrillation,” Seutter says. “Until now, there have been few options except anticoagulation medicines.”

The whole procedure takes an hour or two, Seutter says. The patient generally stays overnight in the hospital and then goes home, the risk of stroke dramatically cut. After the procedure is completed, patients can go back to normal activities without any limitations. It has a success rate of about 95 percent.

There are other techniques to tackle the left atrial appendage. Often, surgeons will just remove it if a patient undergoes bypass surgery. There are also devices used to obstruct it. One such device is used at Sentara Norfolk General Hospital—the WATCHMAN is a mesh piece that is threaded through the heart to open up the appendage and trap blood clots.

But occlusion devices such as the WATCHMAN are not fail-safe. While they have been shown to be effective, there have been some safety issues—clotting can still occur around the device, and there have been incidences of them becoming dislodged within the heart or not being placed correctly, requiring more surgery to fix the problem. They also still require use of a blood thinner for a time after implantation. And the device, although tiny, is made of metal and stays in the body permanently.

With the LARIAT, nothing is left behind after the suture dissolves. About 900 LARIAT procedures have been done nationwide since the FDA approved it a year ago. Right now, it’s only approved for patients who can’t tolerate blood thinners, although Seutter says the possibility for wider use does exist.

“There are many, many patients out there” who could benefit from the procedure, Seutter says. “Potential candidates are numerous.” Even for people who can tolerate blood thinners, the medication is one they have to take for their lifetime, with constant monitoring. With Coumadin, the most commonly used blood thinner, the dose often has to be adjusted, and there are dietary restrictions. There are also risks of bleeding, especially in older patients, according to Columbia University Medical Center’s Center for Interventional Vascular Therapy.

“The LARIAT is proving to be an excellent alternative to patients who are facing a lifetime of blood-thinning medications, who are required to be monitored by their doctor frequently, or who might be facing more invasive open-heart surgery,” says Chung. For Ellenor, who also suffers from hypertension and has a pacemaker and a defibrillator, having the LARIAT procedure means she no longer has the constant fear of having a stroke. That means she’s back tobenjoying her life—doing yardwork and spending time with her three grandsons.

Prior to having the procedure, Ellenor was at “a very high risk” for a stroke, Seutter says.

“As soon as I woke up, I was so relieved not to have that monkey on my back,” Ellenor says. “This doesn’t mean I’m not going to have a stroke; this puts me back in the playing field. This puts me at a lower risk. I thank God every day for this procedure.”

Seutter and Chung are actively seeking candidates who may be eligible for the LARIAT procedure.